Bring Me Sunshine

2002 Article

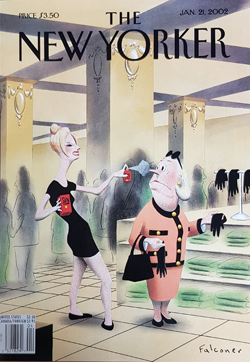

The front cover

Hamish McColl

Sean Foley

Now, at the Wyndham's Theatre, they are back at their stock-in-trade with some cunning hokum entitled "The Play What I Wrote," a sort of anti-homage to the late, great English double act Eric Morecambe and Ernie Wise, who teamed up in the early forties and who, from 1954 to 1984, primarily through a variety of television shows, corrupted the English public with a pleasure that made them among the most beloved comedians of the postwar era.

The show - which includes nonsense songs, surreal dance numbers, a visit from a mystery guest, and the staging of a terrible play ostensibly penned by McColl ("A Tight Squeeze for the Scarlet Pimple") - takes its energy and much of its shape from the arsenal of Morecambe and Wise's genial flimflammery, and it brings the antic spirit of English music hall into the twenty-first century.

"There are funny lines, but no funny men," Eric Morecambe told Kenneth Tynan in 1973. But Morecambe, who died in 1984, was a funny man. He was tall, bespectacled, rambunctious, and swift. Rubber-legged, he had the extra advantage of looking goofy in almost any costume, especially a posh one. He had the clowns rogue gene.

Wise, who died in 1999, did not. He was short, conventionally good-looking, and somewhat vacant. Where Morecambe was incorrigible, Wise was sedate. Light needs shadow to intensify its brilliance, and so it is with comics, which is why Dame Edna employs the deadpan Madge, and the blowhard Oliver Hardy was partnered by the Milquetoast Stan Laurel.

Wise’s pretensions to artistic and intellectual authority impelled Morecambe to take liberties; his gravity showed off Morecambe's grace. In other words, Wise was the prose that allowed Morecambe's poetry. Everything that Morecambe touched with his exaggerated gestures - his thick black glasses, his hat, the curtain (especially the curtain) - became an occasion for zany upstaging and for an exhilarating mockery of decorum. Together, like all great comedy teams - Martin and Lewis, Burns and Allen, Abbott and Costello - Morecambe and Wise cut a risible silhouette: they were a collection of physical and psychological opposites, which combined to present the world with a single comic psyche.

The brashest and most interesting conceit in "The Play What I Wrote" is that neither of the contemporary clowns wants to be Wise; both vie to be the madcap, scene-stealing Morecambe. The opening of Act II simulates the finale of the long-running TV series "The Morecambe and Wise Show," with Foley and McColl in top hats and tails dancing backward down neon-lit stairs to the signature tune "Bring Me Sunshine." When they turn to face us at the end of the number, both Foley and McColl are wearing Morecambe's black glasses. It's a great sight gag.

"The Play What I Wrote" also raises the knotty issue of which member of The Right Size is funnier, who is the ticket and who the passenger - an inevitable undercurrent both of a double act's curious symbiosis and of its neurosis. In this battle of nitwits, McColl, who apparently hasn't raised a laugh since 1997 (the legendary titter was caught on tape and is played for us), is the loser. He decides to throw in the towel and break up the team, which provides The Right Size with its own opportunity to send up theatrical artifice.

McCOLL: Sean, I'm retiring from show business.

FOLEY: You're only saying that to cheer me up.

MCCOLL: Its true.

FOLEY: Where are you going?

MCCOLL: I don't know yet.

FOLEY: Say your next line and find out.

MCCOLL: Eastbourne.

FOLEY: There you go.

But before he leaves, The Right Size - with the help of Toby Jones, a pug-nosed jack-in-the-box who bobs up variously as the show's producer, David Pugh, Daryl Hannah, and the people of France - manages some rollicking moments. As McColl gnashes his teeth about his inability to get more than "inaudible laughs" - "I am not funny, and I have no hope of ever being funny" - Foley keeps popping up behind him with cue cards to undermine the shaggy sob story: "PROFESSIONAL SUICIDE," "PATRONISE HIM," "BLOND GIRL . . . STALLS . . . ROW C . . . PIZZA HUT . . . FIVE MINUTES."

Every laugh is Foley's, but McColl magnanimously thanks the audience. "I am even grateful to Sean for giving me this moment alone with you, and not using it as an opportunity to make another cheap gag," he says. It's wonderful vaudeville folderol.

Such exercises in liberty are hard to pull off, but the level of oxygen that this evening generates is greatly increased by the deft direction of Kenneth Branagh, who has borrowed from such far-flung sources as James Thurber's lurking behemoth animals and Buster Keaton's collapsing house in "Steamboat Bill, Jr." And Eddie Braben, who wrote much of Morecambe and Wise's trademark daft cross talk, has been imported to add authentic dopiness to Foley and McColl's punning badinage.

"The time is 1759," McColl says, as he introduces his awful play. Foley interrupts: "Call it six o'clock."

For Morecambe and Wise, whose only higher education took place on-stage, comedy was business (they referred to playing the provinces as "bank raids"). They had nothing else. "For Ernie and I to play one minute without a laugh is murder. It is fear" Morecambe told Tynan. The urgency of their commitment was what sometimes elevated their act to the purity of metaphor and made them poetic. McColl and Foley, on the other hand, are university wits - men with options. They aspire to art, and at times they strain for the resonance of metaphor, which is why their shrewd act, even when it succeeds, seems a little earthbound.

This self-consciousness is apparent from the first beat. Taking a page from Morecambe and Wise's book, "The Play What I Wrote" begins and ends with the pair together in bed - a neat correlative for their comic interdependence. At the opening, as Foley strums a ukulele, they sing a nonsense song that concludes, "I'm dreaming of a hope / Hoping for a light /To finish a ridiculous song / About a song / About a dream." The song, which is uncharacteristically oblique, is an attempt to deconstruct Morecambe and Wise's high jinks - their dreamscape of caprice, in which gestures become a semaphore of joy, and ignorance, insult, humiliation, and ambition have no consequences but delight.

At the finale, as the men get comfortable under the covers, they ponder McColl's play and the performance of the mystery guest (the week I saw the show, it was George Cole, the hatchet-faced star of "Minder," playing the Comte de Toblerone).

The show ends with McColl planning yet another wretched play; the moment works as both sentiment and its antidote, a testament to two hapless souls bound together and killing time.

FOLEY: YOU know what you are? Brave beyond words.

MCCOLL: That's a good title, that is. I'm going to start on that in the morning. It's going to be about a Red Indian who can't speak.

(A police siren. They turn to each other.)

MCCOLL AND FOLEY: He won't sell much ice cream going at that speed.

"God they were funny," McColl and Foley add. Yes, they were. And so are The Right Size. But, no matter how hard they try to sidestep the issue, they are still lumbered with the impossibility of impersonating an incomparable act - they are neither quite themselves nor quite the act they honor. The audience is entertained but not, finally, inspired. At the curtain call, McColl and Foley surrender to the imperatives of nostalgia: they sing the song that was the simple and profound contract Morecambe and Wise made with the public and with each other at the end of every show—"Bring me fun / Bring me sunshine / Bring me love." Morecambe and Wise spent a lifetime defining their uniqueness; this remains the biggest challenge facing McColl and Foley. "The Play What I Wrote" is their greatest success so far, but not, I'd like to think, their greatest accomplishment.

© The New Yorker 2002